Part II

Romanov, Yermash, Sisov and all those within the decaying soviet totalitarian system were bereft of ideas and their only guiding principle was to try and not make mistakes which superiors might deem contrary to Bolshevism – which they themselves probably did not even understand. The removal of Romanov was just one symptom of this.

Out of these early contradictions and the pressures with which Tarkovsky had to contend to get his films made, he forged the artistic and creative principles by which he knew he had to work. In 1970 he wrote:

One doesn’t need a lot to be able to live. The great thing is to be free in your work. Of course it’s important to print or exhibit, but if that’s not possible you still are left with the most important thing of all – being able to work without asking anybody’s permission. However, in cinema that is not possible. You can’t take a single shot unless the State graciously allows you to. Still less could you use your own money. That would be viewed as robbery, ideological aggression, subversion.

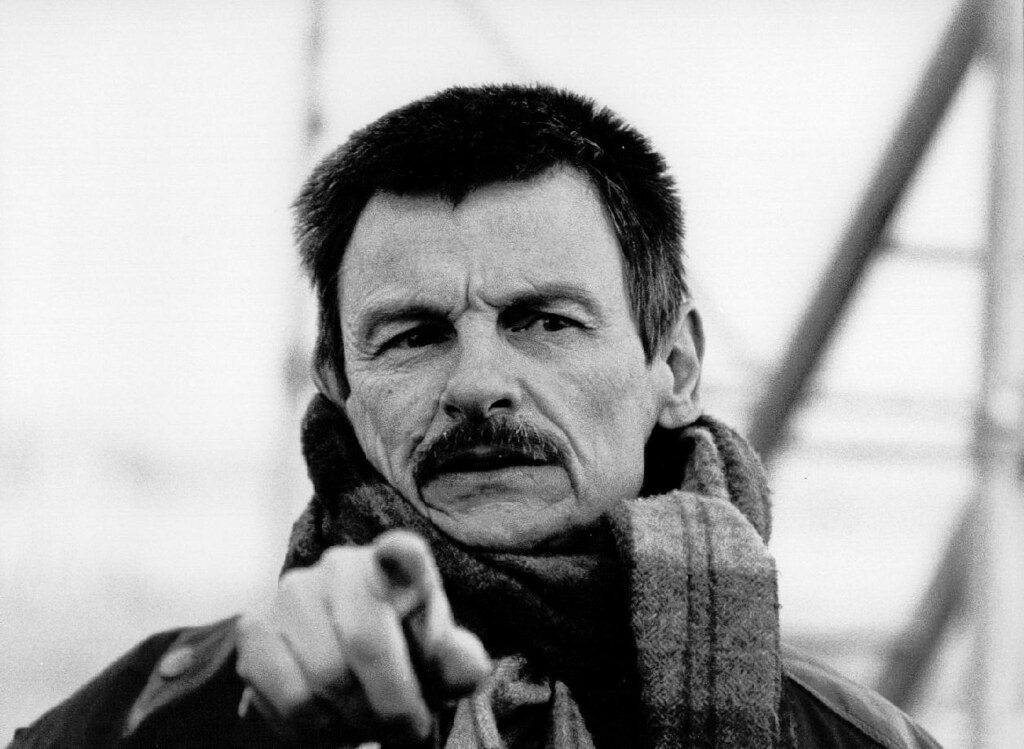

Stalker, Tarkovsky’s last film made in the Soviet Union, is based on Roadside Picnic, a story by the Strugatsky brothers. But in Tarkovsky’s hands it probes the depths of what the film-maker saw as the fundamental crises of the modern world: the rift between natural science and belief; the future of mankind living with the atomic bomb; and, ultimately, the dim glimmer of hope still left to man.

What these four films (Andrey Rublev, Solaris, Mirror and Stalker) up to this point revealed – and his enemies in the system sensed this, but did not understand it – was Tarkovsky’s Christian faith and his realisation of the totally corrupting influence of Marxist materialism. Mirror, so beautiful but equally obscure to them, was more personal. But they also hated it. However, by now his international acclaim was such a huge factor that their obnoxious treatment had to be camouflaged.

In his diaries at that time he revealed his soul and his devastating critique of the system he lived under.

By virtue of the infinite laws, or the laws of infinity that lie beyond what we can reach, God cannot but exist. For man, who is unable to grasp the essence of what lies beyond, the unknown – the unknowable is GOD. And in a moral sense, God is love.

His reading of Marxism and the faltering regime he had to try to live and work under is summed up as follows:

Man is estranged. It might seem that a common cause could become the basis of a new community; but that is a fallacy. People have been stealing and playing the hypocrite for the last fifty years, united in their sense of purpose, but with no community. People can only be united in a common cause if that cause is based on morality and is within the realm of the ideal, of the absolute…Because each one only loves himself… Community is an illusion, as a result of which sooner or later there will rise over the continent evil, deadly, mushroom clouds…An agglomeration of people aiming at one thing – filling their stomachs – is doomed to destruction, decay, hostility.

‘Not by bread alone,’ he concluded.

Elsewhere he said, materialism – naked and cynical – is going to complete the destruction.

Despite the fact that God lives in every soul, that every soul has the capacity to accumulate what is eternal and good, as a mass people can do nothing but destroy. For they have come together not in the name of an ideal, but simply for the sake of a material notion… Man has simply been corrupted…. Those who thought about the soul have been – and still are being – physically eliminated.

In watching a Tarkovsky film one has to take note of the way in which he wants viewers to respond. In this we are not far from Christopher Nolan’s expectations of his audiences. Nolan Admired Tarkovsky and his work, and particularly Mirror.

Tarkovsky described what he saw as a basic principle of film-making… the mainspring is, I think, that as little as possible has actually to be shown, and from that little the audience has to build up an idea of the rest, of the whole. In my view that has to be the basis for constructing the cinematographic image. And if one looks at it from the point of view of symbols, then the symbol in cinema is a symbol of nature, of reality. Of course it isn’t a question of details, but of what is hidden.

Like Nolan, Tarkovsky makes demands on his audience. Viewers have to, as it were, learn a cinematic language which mainstream Hollywood does not teach or even know.

The battles for distribution continued with Yermash. But there were some signs of a thaw and Tarkovsky was eventually able to make two films abroad, one in Italy and one in Sweden.

He began to see his battles as a cross Christ asked him to bear. He wrote of the Cross and identified his woes with Christ’s Cross. At one point he saw himself facing two years of misery: with Andriushka at school; and Marina, and Mother, and Father. It is going to be hell for them. What can I do? Only pray! And believe.The most important thing of all is…to have faith in spite of everything, to have faith.

We are crucified on one plane, while the world is many-dimennional. We are aware of that and are tormented by our inability to know the truth. But there is no need to know it! We need to love. And to believe, Faith is knowledge with the help of love.

Tarkovsky was allowed to travel to Italy in the 1980s to shoot Nostalgia. This was a Soviet-Italian co-production. The theme is, however, typical of the Russian dilemma: that of the artist abroad, smitten by homesickness, unable to live in his country or away from it — the very fate that befell Tarkovsky himself in the last years of his life. It was even more painful still for him because the authorities restricted the movement of his family and starved him of financial support. It was not until the end of his life that they allowed his young son, Andriushka, to be with him.

His time in Italy in 1980, apart from the creative work he did there on Nostalgia, was spiritually enriching for him. Two extraordinary events in particular highlight this. One was his visit to the Holy House in Loreto. Of this he recorded something very personal in his diary.

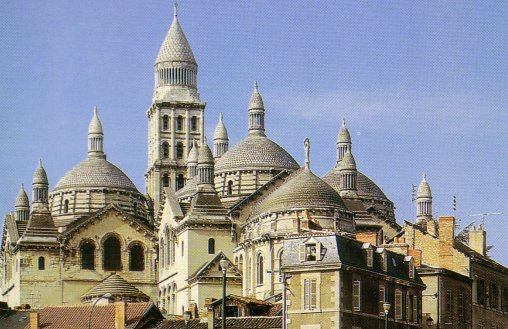

An amazing thing happened to me today. We were in Loreto where there is a famous cathedral (rather like Lourdes) in the middle of which stands the house in which Jesus was born (sic), transported here from Nazareth. While we were in the cathedral, I felt it was wrong that I can’t pray in a Catholic cathedral; not that I cannot, but that I don’t want to. It is, after all, alien to me. Then later, quite by chance, we went into a little seaside town called Porto Nuovo, and into its small, tenth century cathedral. And what should I see on the altar but the Vladimir Mother of God.

Apparently some Russian painter had, at some time, given the church this copy of the Mother of God of Vladimir, evidently painted by him.

I couldn’t believe it: suddenly to see an Orthodox ikon in a Catholic country, when I had just been thinking about not being able to pray at Loreto.

It was wonderful.

The second event he recorded as follows:

Today I relaxed while Tonino finished dictating his script. I went to St. Peter’s Square. I saw and heard the Pope’s appearance in front of the people-the crowd filled the entire square with flags, banners and placards. It’s odd that although I was surrounded simply by large numbers of curious people, such as foreigners and tourists, there was a unity about them which impressed me deeply.

There was something natural, organic in it all. It was obvious that all these people had come here of their own free will. The atmosphere reigning in the Square made that perfectly clear.

I also felt it was wonderful that as I was wandering round the streets, before going by chance into St. Peter’s Square, I had been thinking that today was Sunday and what fun it would be when I got back to Moscow to be able to say that I had been present at a Papal audience at the Vatican.

He also recorded some moments of prayer in his diaries. One such was this conversation with God:

Lord! I feel You drawing near, I can feel Your hand upon the back of my head. Because I want to see Your world as You made it, and Your people as You would have them be. I love You, Lord, and want nothing else from You. I accept all that is Yours, and only the weight of my malice and my sins, the darkness of my base soul, prevent me from being Your worthy slave, O Lord!

These thoughts of death – he was never really in good health – were noted when he was battling with the authorities over the content of Stalker, a film in which the protagonist seeks unsuccessfully to open the minds of his two pilgrim companions to the meaning of our existence:

If God takes me to himself I am to have a church funeral and be buried in the cemetery of the Donskoy Monastery. It will be difficult to get permission. And no one is to mourn! They must believe that I am better off where I am. The picture is to be finished according to the pattern we decided for the music and sound. Lucia must try and tidy up the end of the bar scene. ‘The Room’ should include the new text from the notebook (the sick child) plus the old one, written for the scene after the ‘Dream’.

At the end of 1985, after the release of Nostalgia, again to international acclaim, he completed the shooting of his last film, The Sacrifice, in Sweden. Described as a parable by Tarkovsky, the story revolves around a family awaiting an impending nuclear catastrophe in a remote Scandinavian seaside location. The paterfamilias prays and offers himself to God as a sacrificial victim to save the world from the impending disaster. It is a profoundly mysterious, reflective and beautiful work, regarded by some as the artist’s masterpiece.

Andrey Tarkovsky returned to Rome after completing it. Already afflicted by the cancer to which he succumbed a year later, he died on 29 December 1986, at a Parisian clinic. His last diary entry was made on 15 December. He is buried in a graveyard for Russian émigrés in the town of Saint-Geneviève-du-Bois, France.